Executive Summary

The twelve year National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 was introduced in February, 2011. The National Plan was designed to combat and reduce all forms of assault and domestic violence perpetrated against women and children. A budget in excess of $840 million was allocated to the task; however, the exact amount of funding from the commonwealth, states and territories seems largely impossible to determine.

A number of macro evaluations of the National Plan and micro evaluations of individual programs have been conducted. Whilst some suggest the Plan has been successful, most reveal a lack of any substantial evidence. Evaluation methodologies are questionable, with many evaluation results contradicting what the statistics show, especially for Indigenous communities in Central Australia.

Most evaluations focus on qualitative self-assessment of service providers and funded agencies using limited surveys and a surfeit of anecdotal evidence. Yet they fail to collect or assess quantitative statistical material, and pay scant attention to rigorous statistical analysis, which in the main clearly demonstrates that the programs have met with little success in curbing rates of Indigenous violence against women.

As a result, it is difficult to know with any real certainty to what extent the National Plan has been successful in achieving its aims, and therefore equally difficult to adjust policy settings to better target effective solutions in reducing violence.

Introduction

Government funded agencies have an obligation to be accountable to both government and the community for how taxpayer funds are spent, and of even greater importance, to ensure that funded programs are effectively achieving what they are paid to do – in other words – are they actually making a positive difference to the problems they are funded to solve, and if so, how can we be sure?

In relation to Indigenous programs specifically, in 2016 Sarah Hudson noted that of 1082 indigenous-specific funded programs at the Commonwealth, State, Territory and NGO levels “less than 10% (88) … had been evaluated … and of those programs that were evaluated, few used methods that actually provided evidence of the program’s effectiveness.”[1]

Again, in 2017, Hudson observed that “Analysis of 49 Indigenous program evaluation reports found only three used rigorous methodology … . Overall, the evaluations were characterised by a lack of data and the absence of a control group, as well as an over-reliance on anecdotal evidence.”[2] These are damning indictments, but has anything changed?

The twelve-year longitudinal National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan) introduced in February, 2011, is a case in point. With this multi-million dollar National Plan, are there reasons to think that Hudson’s observations may still apply, especially in relation to Indigenous programs?

As Hudson noted of the 2011 census, approximately 65% of Indigenous people are employed and live in major urban centres, 22% are welfare dependant, with many living in regional areas, and 13% are also mainly welfare dependant, living in remote areas on Indigenous land with limited employment opportunities.[3] There are very different issues for Indigenous peoples based in inner urban capital cities as opposed to remote areas, where Indigenous experiences of domestic violence and assault is appreciably worse.

This paper specifically addresses the impact of the National Plan upon Indigenous Australians in Central Australia. It broadly critiques two macro and three micro evaluations, with a focus upon efficacy within Indigenous populations, specifically in the remote region of Alice Springs.

The National Plan

In 2008 the Australian government established the ‘National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children’. The new Council’s goal was to formulate an “evidence-based plan”[4] to reduce violence against women and children. March, 2009, saw the release of the report Time for Action: The National Council’s Plan for Australia to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2009–2021.[5] The report outlined a long-term strategy for all Australian State Governments and Territories to tackle violence against women and children, (and notably, not men), with the Commonwealth Government taking a lead and coordinating role.

After extensive Australia-wide consultation, the new National Plan was endorsed by all states and territories and the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). Broadly, the plan aims to ensure that over the twelve year life of the plan, fewer women and children will experience violence, and they can live more safely. The First Action Plan (2010-2013) describes the National Plan’s central goals to be “to reduce violence against women and their children and to improve how governments work together, increase support for women and their children, and create innovative and targeted ways to bring about change.[6] A further goal is to be “a significant and sustained reduction in violence against women and their children.”[7]

The National Plan further describes six desired ‘national outcomes’ over the 12 year period:

- Communities are safe and free from violence.

- Relationships are respectful.

- Indigenous communities are strengthened.

- Services meet the needs of women and their children experiencing violence.

- Justice responses are effective.

- Perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account.[8]

Curiously, a reduction in the number or rate of domestic violence and sexual assaults was not listed as a national outcome, but is noted in the Fourth Action Plan as below. The National Plan is to be implemented through four three-year plans as summarised below by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO).[9]

- First Action Plan (2010–13) — Building a Strong Foundation − focused on building an evidence base and establishing frameworks to achieve attitudinal and behavioural change.

Initial commitment of $87.3 million over three years. - Second Action Plan (2013–16) — Moving Ahead − focused on consolidating the evidence base and strengthening existing strategies.

Additional $102.6 million over three years. - Third Action Plan (2016–19) — Promising Results − intended to deliver results from the long term initiatives implemented during the first two Action Plans.

Additional $103.9 million over three years. - Fourth Action Plan (2019–2022) — Turning the Corner − expected to see the delivery of tangible results in terms of reduced prevalence of domestic violence reduced proportions of children witnessing violence, and an increased proportion of women who feel safe in their communities.

Additional $328 million over three years.

The Budget

The first three plans have concluded, with the fourth plan being half way into its term. To date this combined Commonwealth budget is $621.8 million, plus a further $101.2 million announced in 2015 for a ‘Women’s Safety Package’, making a remarkable total of $723 million dollars.[10] However, in announcing further funding in 2019, the Commonwealth noted they were bringing “the total invested by our Government to more than $840 million since 2013.”[11]

It remains quite difficult to ascertain the precise amount of funding spent on the National Plan as a comprehensive Commonwealth Budget does not seem to be available. It is therefore difficult to track the specific expenditure of these funds and to know how or where all this money has been spent, if it has been spent at all.

Where is all the money going? Four ANROW’s research projects, valued at over $684,000 and all University-based, are worthy of note. (See Appendix A). Research is necessary of course, but will this amount of expenditure actually produce a long-term benefit and assist in reducing Indigenous domestic violence and assaults. There would appear to be no evidence that it has.

Evaluations

As the National Plan draws to a close, it is timely to examine the efficacy of the multi-million dollars of expenditure in program implementation, and to assess in part its efficacy for Indigenous Australians.

The National Plan, and all four Action Plans, emphasise the need for a strong ‘evidence base’, so in reality what does that mean? Under the First Action Plan[12], governments agreed to begin building the evidence base by:

- Establishing a National Centre of Excellence to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (now the Australian National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety – ANROWS) to drive research efforts over the life of the National Plan;

- Commencing work to develop nationally consistent data definitions and collection methods as part of a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework, to be operational by 2022[13];

- Conducting a Personal Safety Survey and the National Community Attitudes towards Violence Against Women Survey on a four-yearly rolling basis;

- Establishing an evaluation plan for the life of the National Plan.

There was a clear commitment to establish a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework, and this has been achieved. The Australian Bureau of Statistics has established a ‘Directory of Family, Domestic, and Sexual Violence Statistics’ yet it remains to be seen how well it is being utilised.[14]

Contained within the First National Plan are the ‘Measures of Success’ pertaining to the Indigenous component (Outcome 3) of the Plan, as follows:

The success of Outcome 3 will be measured by reduction in the proportion of Indigenous women who consider that family violence, assault and sexual assault are problems for their communities and neighbourhoods; and increase in the proportion of Indigenous women who are able to have their say within their communities on important issues, including violence.[15]

This measure of success does not make any reference to measuring the rise or fall in actual numbers of domestic violence cases, merely an assessment of how Indigenous women feel about assault and sexual assault being a problem, and if they feel they are able to have a say about it.

In 2014, a consultancy firm was engaged to develop an Evaluation Plan of the National Plan.[16] Their proposed approach is as follows:

The success of the National Plan cannot be measured by a single evaluation activity. This Evaluation Plan sets out a range of activities:

1. Reviews of three-yearly Action Plans: these will reflect on the success of the previous Action Plan to inform the development of the next Action Plan.

2. Annual progress reporting: these are a key monitoring, accountability and communication activity under the National Plan.

3. Evaluation of flagship activities: this involves the evaluation of key national initiatives under the National Plan.

4. Underpinning evaluation activities: this includes analysis of the considerable and increasing amount of data available to measure women’s safety, including the Personal Safety Survey and National Survey on Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women.

With these evaluation activities, governments and the community will be able to measure the effectiveness of the National Plan every three years and at the end of the National Plan’s 12-year lifespan. [17]

Again, note that with the oblique reference to “data” in point four, there is no reference to examining the actual statistics in national, state or territory jurisdictions as to the rise or fall in domestic violence numbers. Indeed, point four’s reference to ‘data’ majors on safety and attitudinal surveys.

Formal Evaluations Conducted

This paper shall focus on five evaluations, two being overall national studies (KPMG and ANAO), and three being localised to Alice Springs (one UNE, and two Tangentyere studies.) Along with Department of Social Services (DSS) and COAG Progress Reports, two formal external evaluations of the National Plan have been conducted, one by KPMG in 2017 on the Second Action Plan, and one by the ANAO on the first three action plans, tabled to the Government in July 2019. Both evaluations have highlighted concerns about the progress made towards the National Plan’s outcomes, and the ability of the DSS to evaluate its efficacy.

The 2017 KPMG Evaluation[18]

The KPMG evaluation conducted “desktop research of government and non-government programs in each state and territory” and “draws largely on, existing research and evaluations already undertaken” with their evaluation having relied “on advice from stakeholders gathered through workshops and surveys across all jurisdictions” [19]

KPMG distributed an online survey to service providers in late-2015, with a response rate of 44%, receiving 136 completed surveys.[20] It is not known who the responder agencies were, or if any of them were Indigenous. A range of workshops were also held across Australia that were almost entirely ‘in-house’, consisting mainly of departmental staff and a small sample of NGO’s. The KPMG evaluation apparently did not speak with any clients or consider any domestic violence statistical analysis. Such a deskbound survey analysis of service provider agencies coupled with no statistical data cannot be considered an effective evaluation.

There are three Action items (Nos. 8 to 10) that specifically pertain to Indigenous elements of the National Plan, their efficacy being determined by the responses of 136 unknown funded agencies surveyed across Australia. They are not client responses, so are from the outset unreliable.

Action 8

Meet the needs of Indigenous women and their children through improving access to information and resources, and providing avenues for advocacy and leadership. (KPMG Report, p 43.)

COMMENT: This action was assessed by KPMG as ‘mostly complete’ – despite 33% of survey respondents saying that the action was ineffective and a further 37% considering it to be “somewhat effective”. If 70% thought the action item to not be effective, how can it be ‘mostly complete’?

Northern Territory Government response to Action 8

The NT Government offered a number of services aimed at meeting the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children. Under the Second Action Plan, the NT Government signed up to support Our Watch. The Our Watch certificate of commitment ensures that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children from remote regions are a part of Our Watch’s strategic direction. (KPMG Report, p 44.)

COMMENT: This of course tells us nothing about the efficacy of what was actually done. Further, Our Watch is not a provider of services to Indigenous people, so the “certificate of commitment” to “strategic direction” is merely an academic gesture.

Action 9

Improve outcomes for Indigenous Australians through building community safety.

Action 9 aimed to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children are able to enjoy the protection that the law, in principle, should provide and also to further develop community safety to reduce violence against women and their children. (KPMG Report, p 47.)

COMMENT: Assessed by KPMG as ‘partially complete’, however, as noted below:

Effectiveness of Action 9

The effectiveness of this Action was not assessed because no specific activities were identified by jurisdictions against this Action as part of the Second Action Plan. (KPMG Report, p 48.)

COMMENT: It would seem rather odd that by 2015 no jurisdictions had taken any National Plan action regarding ‘improving outcomes for Indigenous Australians through building community safety’, so it is difficult to understand how it can be assessed as ‘partially complete’.

Action 10

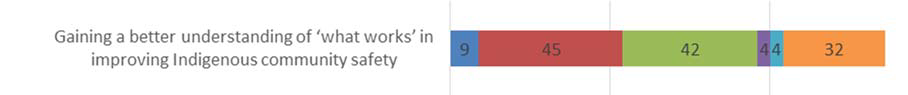

Gain a better understanding of ‘what works’ in improving Indigenous Community Safety.

COMMENT: Assessed by KPMG as ‘partially complete’. Further detail is contained below:

Completeness of Action 10

Action 10 aimed to develop a national picture of ‘what works’ to make Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families safer and incorporate this into new evidence based policy.

Intention and Government commitment

For Action 10, Governments’ intention was to improve policy and service delivery based on a recognised need to understand what works in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, particularly in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. (KPMG Report, p 48.)

Most jurisdictions conducted consultations, reference groups and other methods of engagement to gain a better understanding of ‘what works’ in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Some of the programs delivered across jurisdictions were specifically designed to gain a better understanding of the issues and solutions to family violence and sexual assault that are particular to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. (KPMG Report, p 49.)

Northern Territory Government response to Action 10

The NT Government maintained its commitment to deliver the Domestic and Family Violence Reduction Strategy. As part of this strategy, the NT Government used Local Reference Groups in Alice Springs, Darwin, Katherine and Tenant Creek to drive the strategy on the ground and enable the collection of local knowledge from service providers and police to support victims of domestic and family violence.

The non-government sector is heavily involved in the Local Reference Groups and participates in monthly meetings to ensure local expertise informs the implementation of the Strategy. There are 62 government organisations and NGOs represented in the Local Reference Groups including 19 government organisations, 16 Aboriginal organisations and 27 NGOs. The NT Government’s Domestic Violence Directorate chairs these meetings and is the conduit of information between service providers, local organisations and the NT Government regarding domestic and family violence policy initiatives and program development and implementation. (KPMG Report, p 49.)

COMMENT: None of the above information provides any indication of the efficacy of any of the program initiatives. It is merely a description of what has occurred, not of how effective it was. It cannot be considered to be an evaluation at all.

Effectiveness of Action 10

Action 10 was considered somewhat effective for gaining a better understanding of ‘what works’ in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Almost half of the survey respondents believed that Action 10 had some degree of effectiveness: 31 per cent of survey respondents thought that Action 10 was somewhat effective while 3 per cent indicated Action 10 was very effective and another 3 per cent indicated that Action 10 was extremely effective. In contrast, 33 per cent of survey respondents considered Action 10 to be not very effective and a further 7 per cent considered Action 10 to be not at all effective. (As shown in raw numbers in Figure 1 below.)

Figure 1: Effectiveness of National Plan Action 10

(KPMG Report, p 50.)

COMMENT: Given the known flaws with surveys, the KPMG results are all the more worrisome. Can they be relied upon at all? On the face of it, 40% of the agency respondents are of the view that Action 10 is not (very) effective at all, whilst 31% thought it a little effective, with a mere 6% of respondents (8 out of 136 agencies) thinking it effective. 23% (32 agencies) were “unsure”! (Incidentally, 37% of respondents is not “almost half”.) If the agencies are not very convinced of the efficacy of their own programs, what must the clients think, and what is actually happening towards positive change ‘on the ground’. The implication is ‘not much’.

The above ‘evaluation’ results are based upon a self-selected national sample size of only 136 respondent agencies to an on-line survey, respondents with an unknown number of Indigenous participants, perhaps if any, who were ostensibly ‘evaluating’ the effectiveness of the whole National Plan program for Indigenous Australians.

Given the methodology of the KPMG evaluation, there is no possibility that it can shed any reasonable light of the ‘on the ground’ effectiveness of the Nation Plan, especially in relation to Indigenous programs. It is thoroughly inadequate.

The 2019 Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) Evaluation[21]

In June, 2019, the Auditor-General presented the Commonwealth government with an independent performance audit report on the National Plan. Overall, the ANAO report found that “The Department of Social Services’ effectiveness in implementing the National Plan … is reduced by a lack of attention to implementation planning and performance measurement” and that “performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting is not sufficient to provide assurance that governments are on track to achieve the National Plan’s overarching target and outcomes … the department will need to develop new measures of success and data sources, plan for evaluations beyond the National Partner initiatives and improve public transparency. [22]

Along with Figure 2 below, the ANAO Report concluded that “The department has funded research to build the evidence base. This research program as a whole does not provide sufficient focus on program evaluation and research synthesis to inform policy decisions and program improvements that contribute to achieving the National Plan’s outcomes.”[23]

Figure 2: ANAO assessment of Effectiveness of the National Plan

3.29 Overall, the research that has been funded to date has largely focused on gaining a better understanding of the experience of people from particular cohorts or in specific contexts, with limited emphasis on evaluating which services are working, for whom and in what contexts. In the small number of projects focused on reviewing or evaluating a service or service delivery approach, the ANAO found limited evidence of consideration of cost effectiveness. [24] (Highlighting added.)

ANAO findings included that due to the currently limited performance measures, and in anticipation of the Fourth Action Plan or any future National Plan, the department should “consider developing short- and medium-term outcomes, new measures of success and more frequent data collection mechanisms” otherwise, “the ability for jurisdictions to demonstrate the success of the National Plan will be limited” [25] This is described in more detail in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3: ANAO Statement on Monitoring and Evaluating Outcomes

Are appropriate arrangements in place to monitor and evaluate the achievement of outcomes? Evaluations or reviews of National Partner initiatives and of the Second and Third Action Plans have been completed or are planned, but do not sufficiently focus on assessing the achievement of outcomes. The Third Action Plan evaluation methodology proposes assessing the contribution of this plan to the National Plan outcomes, but without robust data, is unlikely to achieve this purpose. The quality of data and assessment of the impacts of actions undertaken across jurisdictions need to be improved to support outcome-focused action plan evaluations. Without these improvements, the overall achievements of the National Plan will not be able to be fully assessed. [26] (Highlighting added.)

There is a consistent theme running through the ANAO report, and that is of ‘limited success’. It is clear that ANAO has very real reservations about the effectiveness and the evaluation of the National Plan.

In summary, it would seem clear that ANAO is concerned about:

- A lack of attention to implementation planning and performance measurement;

- Insufficient performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting;

- Not being able to achieve the National Plan targets and outcomes;

- The need to develop new measures of success and better data sources;

- The need to plan for further evaluations and the improvement of public transparency;

- The failure of the current research approach to sufficiently evaluate programs or synthesise research to inform policy decisions or improve programs;

- The need for changes to determine successful outcomes with more frequent data collection;

- Without improvements, the ability to demonstrate success will be limited. [27]

Whilst written in rather mild bureaucratic ‘government speak’ language, given the amount of funds directed towards the National Plan, ANAO’s observations are a rather damning indictment on both the lack of success of the National Plan and the ineffective way in which it has been evaluated.

The ANAO report only made five recommendations to DSS (see Appendix B) all of which were accepted by the Department. Four of the five recommendations relate specifically to evaluation and outcomes, thus highlighting a clear inadequacy of the existing and previous Action Plans. It remains to be seen how these recommendations will be addressed and implemented.

The 2015 University of New England (UNE) ‘Alice Springs Integrated Response to Family and Domestic Violence project: Final Report’[28]

This comprehensive UNE evaluation report of the provision of family and domestic violence services in Alice Springs is the only evaluation seen to make use of substantial statistical data, or to make any detailed reference to hospital admissions and separations (ie: departures).

Elements of the report focused on hospital admissions pre- and post-Family Safety Meetings (FSM), as a part of the Family Safety Framework (FSF), noting a reduction in domestic violence assault related admissions from 118 cases two years prior to the FSM project down to 96 cases in the two years post FSM project.[29] The report nevertheless noted:

However, based on the hospital records, the FSF does not seem to be protecting women from family violence where no single perpetrator is typically responsible for repeated incidents. From what was recorded, family violence rarely involved the same family member perpetrating successive assaults.[30]

The report shows that for the period 2008 to 2015 the number and rate of Aboriginal female domestic assault victims has continued to escalate, with the number of domestic violence assaults by Aboriginal males substantially escalating.[31] Whilst the report concluded that various projects had made valuable contributions to local service provision, it cannot be argued that rates of domestic violence have decreased as a result. Nevertheless, this comprehensive and thorough report is one of the better evaluations seen and has made valuable use of available statistics.

Alice Springs Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program Evaluation Reports

The Alice Springs Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program lists many resources related to their work[32] and in particular, two evaluation reports, as follows:

Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group Program Evaluation Report. [33]

Nettelbeck’s 36-page 2017 evaluation is based upon reviewing organisational records, holding workshops, focus groups and interviews with clients, client groups, and other stakeholders.[34] The evaluation presents a number of case studies and some ‘journey mapping’. Various self-assessed outcomes are noted, including ‘better understandings’ and ‘improved communication’. Resources developed by the groups have also been listed.

One of the key objectives and achievements noted was that “Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group has complete ownership, control and development over every aspect of the program”, including the Men’s Behaviour Change Program.[35] However, in apparent contradiction, also states they are “not wanting to do things without including them.” (ie: men)[36] What is the men’s role in that program, and is it clear how and if the program contributes to reducing the incidence of domestic violence and assault? Whilst the evaluation is an impressive summary of what the Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group Program has done and is doing, no-where is there any analysis as to whether or not the program has been successful in reducing the incidence of violence against women as a part of the goals of the National Plan.

Whilst the work may be progressive steps in the right direction, it is pleasing to see that Recommendation 2 included “the addition of measurable indicators and data collection methods.”[37]

Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program: A Case Study. 2019 Final Report’[38]

The 61-page 2019 Brown report on the Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program (TFVPP) is another more recent case in point. The evaluation applies a “thematic analysis” to a “Transtheoretical” or “Stages of Change model” to “assess whether it is likely that the program is assisting in the creation of change.”[39]

The evaluation takes a ‘gendered approach’ to its assessment in line with material produced by Our Watch using techniques of participant observation, workshops, focus groups, interviews with clients (‘yarning’ methodologies), and other stakeholders. Using NVivo software for coding qualitative responses, themes were determined and analysed. The report then moves to discussing “the drivers of violence against indigenous women”[40] where the Our Watch mantras of ‘colonisation’ and ‘gender inequity’ are discussed at length.

Whilst Recommendation 1 is to “Improve data collection”[41] of both quantitative and qualitative data, the recommendation is very limited in the type of quantitative data it suggests should be collected and it remains unstated as to how it would be assessed or to what end.

In contrast to the 2015 UNE report, the 2017 Nettelbeck report makes no mention of hospital admissions at all and the 2019 Brown report mentions hospital admissions only in passing by way of background, as below:

Between 2014-2015, the hospitalisation rate of Australian Indigenous women and men for family violence related incidences was 32 and 23 times that of non-Indigenous women and men respectively” [42]

Both reports also contain what can best be described as ideologically driven mantra as found in the ‘Our Watch’[43] and ‘No to Violence’[44] organisations. Indeed, Brown quotes from Our Watch that:

Our Watch recommends that in order to prevent violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) women, programs must challenge misconceptions about violence perpetrated against them. These misconceptions include that violence is a part of traditional Indigenous cultures; that violence against Indigenous women is exclusively perpetrated by Indigenous men; and that violence against Indigenous women is caused by alcohol or other substance abuse (Our Watch, 2018).[45]

It is difficult to see how a denial of Aboriginal ‘old’ and new ‘culture’, blaming white men, minimising the impact of alcohol, and failing to mention personal responsibility, meanwhile focusing upon a blinkered view that ‘gendered drivers of violence’, ‘legacies and ongoing impacts of colonisation’ and ‘inter-generational trauma’ are primarily responsible for Aboriginal domestic violence.[46] Such an approach will likely continue to inhibit real understanding and solutions being found. Indeed, diminishing the so-called ‘misconceptions’ can have seriously deleterious consequences, given that a 2011 Australian Institute of Criminology paper reported that:

… 75 percent of Indigenous female sexual assault victims did not report the offence because of fear, either of repercussions or police attitudes … (and that) … fear of violence and ‘payback’, or culturally related violent retribution, were the most commonly cited reasons for women not reporting violent victimisation.[47]

It is clear that misattributing cause and failing to acknowledge realities can cost Aboriginal women their lives.

If the current anti-male mantra of blaming colonisation and inter-generational trauma for violence against Aboriginal women continues, it is difficult to see how any real progress can be made in reducing violence. Men will not come on this journey if they are always held to blame.

The 2017 Tucci report Strengthening Community Capacity to End Violence: A project for NPY Women’s Council continues in a similar vein,[48] although there is not the scope to fully review that report in this paper.

Rather than focussing on ideological mantras, the focus should rely upon a more comprehensive view of history, and all of the facts. Further, rather than scapegoating one gender and attributing blame for their actions to a selective and distorted version of the historical past, all people must accept responsibility for their own present personal behaviour. Only will this assist in identifying and addressing the root causes of the very high incidence of all violence in Aboriginal communities.

All three of the apparently ideologically-laden Nettelbeck, Brown, and Tucci reports stand in stark contrast to the more balanced 2015 UNE Putt, Holder & Shaw report which avoids ideology almost completely, focussing just on the facts.

If more such objective research could be done, coupled with comprehensive quantitative data collection and analysis, then perhaps increased and more effectively targeted early intervention and prevention programs could be rolled out with greater understanding, cooperation and success.

The Problem With Surveys:

Surveys alone cannot be considered a reliable evidence base of program effectiveness for they contain too many variables to be considered an accurate source of information, especially on their own.

Inadequacies in survey design and application are well known. Whilst surveys may be easy to administer and provide for a degree of generalisability, they are nevertheless fraught with error and can be inflexible and lack real validity. For example, inter alia, there may be inadequate response options, have inconsistent rating levels, assume prior knowledge, ask leading questions, contain confusing compound or ambiguous questions, be too long and require lengthy answers that some respondents are unwilling to complete, be unrepresentative and/or have too small a sample size.

For adequate National Plan evaluation, surveys, workshops and interviews can only be a part of the method, not all of it. Clearly, if program effectiveness is to be assessed and validated, most important of all are the numbers – but what numbers?

Statistics and the Need for Numbers

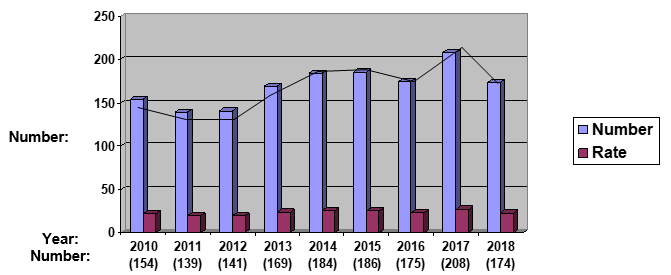

Already both the KPMG and ANAO reports note the relative ineffectiveness of the National Plan, but what do the statistics tell us? As shown in Figure 4 below, the Australia Bureau of Statistics Report 4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018, released in June 2019, notes the following:

Figure 4: Number of Sexual Assault Victims in Australia to 2018[49]

Number of Sexual assault victims continues to increase

Surely the above ABS paragraph is the most damning indictment of all regarding the abject failure of the National Plan and the multi-millions of wasted dollars? The year 2018 was the seventh consecutive year of increase and a 40% increase since 2010.

Drilling down to the Northern Territory figures, the number of overall victims of sexual assault recorded in 2018 decreased by 16% (66 victims), from 426 victims in 2017 to 360 victims in 2018, nevertheless still quite high numbers. This was the lowest number of victims recorded in the NT since 2012 (325 victims).[50]

Whilst on the surface this may appear a good result, it does not tell the whole story, especially in relation to Indigenous sexual assaults, which as shown in Figure 5 below, indicate a steady climb since 2012.

Figure 5: Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Sexual Assaults NT 2010 – 2018[51]

Whilst in 2018 there was a reduction in Northern Territory Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Sexual Assaults, the trend nevertheless remains upwards. The rate shown is per 100,000 of population. The Alice Springs specific domestic violence assault figures are shown in Figure 6 below:

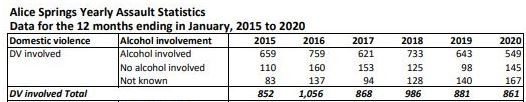

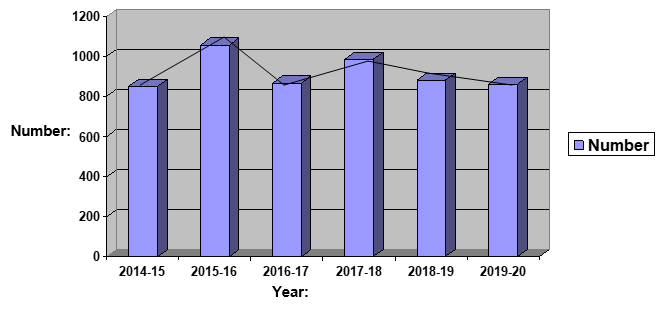

Figure 6: Alice Springs Indigenous Domestic Violence Assaults 2015-2020[52]

NB: In reality, the statistics are actually for the year before; ie: the 2020 statistics are for the 2019 year. Nevertheless, it can be seen that the overall rate of domestic violence and assault remains very high, and for over five years has remained at an average of 917 victims per year. The above statistics are shown visually in Figure 7 below.

These simple statistics give the lie to the evaluation’s claims to ‘success’. Despite the fact that the KPMG and ANAO evaluations state there has been progress in the effectiveness of the National Plan, the statistics clearly state otherwise. In the Alice Springs region there were 852 Indigenous domestic violence cases in 2014-15 and 861 cases in 2019-20, and increase of nine cases. How by any measure, especially given the amount of funding spent, can this be seen as any success or progress? For the multiple millions of dollars being spent, where is the value for money and where is the result?

Put simply – the numbers don’t lie. However, obtaining such numbers is sometimes not so easy. A January 2020 ABC News Australia-wide investigative report about the level of police support for victims of sexual assault was hamstrung by the NT Government’s refusal to supply any statistics or information. The journalists noted that “Northern Territory police refused to supply data for this investigation (and) refused multiple requests for statistics. An application under freedom of information laws was refused on the basis the information was available by request to NT Police.”[53] The NT has a reputation for refusing FoI requests; indeed, in 2019 the NT government was refusing one in four FoI requests, seven times more than Victoria and eight times more than Western Australia.[54] Whilst it is unclear what specific statistics the ABC journalists were seeking, such lack of transparency and refusal to provide information poses a large stumbling block to effective evaluation of the National Plan.

The above experiences are juxtaposed against the fact that quite detailed crime statistics, by location across the NT, are freely available on the NT Police website at: https://pfes.nt.gov.au/police/community-safety/nt-crime-statistics That said, neither is it easy to attribute program effectiveness to broad numbers contained in annualised tables, especially if they do not contain an Indigenous and non-Indigenous breakdown. This is why it is necessary to dig deeper to locate a more specific evidence base, for example:

- Ambulance attendances (victims treated and conveyed to hospital, or not);

- Police attendances (perpetrator arrested and charged, or not);

- Hospital attendances (outpatients treated, including type of injury, and discharged);

- Hospital admissions (inpatients admitted and treated, including type of injury and length of stay);

- Rates of incarceration and re-offending of convicted offenders;

- Distinction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cases in all of the above.[55]

The above figures are not readily available, yet they should be – right across Australia. It is these hard numbers that will provide evidence as to whether or not domestic violence and sexual assault rates are increasing or decreasing, and, ipso facto, if the programs are working and if the funds have been well spent. Program evaluators need to be asking the right questions and collecting the right numbers, not relying on the stories that people tell or the self-assessments performed by funded agencies.

Discussion

Interpersonal and family violence has many driving factors, especially within Indigenous communities. Many causes of such violence are related to, inter alia, excessive alcohol and other drug use (by both males and females), Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, lack of employment opportunities, housing stress, poor health and chronic illness, residual negative Indigenous culture and law, boredom, frustration, poverty and economic inactivity, ineffective over-governance and regulation, inter-tribal disruption and amalgamation, failed ‘homelands’ and ‘self-determination’ policies, welfare dependency and a lack of private land ownership. This list could go on. [56] To combat these various malaises enormous amounts of funding have been allocated and spent, many staff employed, and a lot of local businesses benefitted, but are the National Plan objectives really being met and is there value for money?

Service provider agencies and funded programs cannot be reliably trusted to give unbiased or objective feedback about their own efficacy, as they have a clear conflict of interest. Nor do they likely have the skills to produce detailed statistical research or analysis, perhaps being the main reason that little is undertaken. Whilst clear reporting from such agencies and programs should be required, these should not be relied upon alone as the sole measure of program efficacy. Purtill (2017) describes in great detail how many Indigenous program acquittal and evaluation reports back to Government bureaucrats are often written so as to be either deliberately misleading, or at the very least a stretch of the truth, to ensure that funding continues.[57] In addition, feedback from clients, even with the best of intentions, cannot necessarily be trusted as reliable sources. In any event, they are simply subjective personal opinions and observations, not objective data.

However, to be fair, perhaps the difficulty in obtaining detailed statistics is a part of the reason for relying so heavily on qualitative data. If this is the case, strong efforts should be made for better data collection into specific areas and for the public release of that data. That said, it remains unclear to what extent the ABS’ “Directory of Family, Domestic, and Sexual Violence Statistics’ is being fully utilised.

Further, many of the evaluation reports are lengthy, wordy and turgid, leaving one to wonder who really reads them and to what extent they are ever acted upon; or do they just end up on the shelf gathering dust? Most reports simply tell the reader what’s been done, and how people felt about, or what other people thought about what’s been done. Some other reports may simply be a platform to advance an ideologically driven agenda. This is not serious evaluation and authors often give no real indication as to the actual efficacy of the programs. The failure of effective program evaluation contributes to the lack of improvement in domestic violence reduction rates.

Additional problems arise, in that potential duplication of services is given cursory mention, as services do not wish to be de-funded as a result. Discrepancies between survey results and domestic violence statistics are also rarely mentioned, as that would demonstrate program ineffectiveness. Indeed, subjective survey results often allege considerable improvements, whereas statistical data show deterioration.

How is it that surveys were chosen as the primary data source to measure progress towards the National Plan’s outcomes? Other than the UNE Report (which demonstrated a worsening scenario), why has there been no serious attempt at statistical analysis and why have governments essentially only consulted internally to determine program effectiveness?

Finally, whilst Aboriginal domestic violence has always been a problem, there seem to be few, if any authors, who acknowledge that it was not such an issue during the 1930’s – 1970’s ‘mission era’. The escalation to current levels of sexual assault and domestic violence appear a recent development over the last 30-40 years, and indeed may well be related to contemporary policies of land rights and self-determination, coupled with a radicalised anti-male and anti-colonial ideology. Perhaps these topics are also worthy of further investigation?

Policy Implications

The ongoing problem of domestic violence within Indigenous communities requires effective responses which for the last nine years of the National Plan have proved to be inadequate. Evaluation has focussed on subjective personal surveys and feedback from agencies which cannot provide an accurate picture of real program effectiveness. Evidence for program effectiveness must focus on hard concrete data, not nebulous and ill-defined concepts such as ‘cultural change’ without specific causes identified and remedial actions specified.

Success must be measured by the overall reduction of Indigenous domestic violence and assault incidents as revealed in ABS, police, court, ambulance and hospital statistics. At present, many such statistics are quite difficult to publicly access.

There seems to be a consistent message that National Plan programs, and perhaps especially Indigenous-specific programs, are being inadequately evaluated, and perhaps in some cases may not be evaluated at all.

It therefore appears logical that enormous amounts of taxpayer funds are being spent in misdirected and unaccountable ways with little evidence of efficiency or efficacy. Indeed, what evidence is available seems to demonstrate that for the huge amounts of funding committed, any change in behaviour or attitude seems miniscule. Meanwhile, within many agencies an unhelpful and perhaps counterproductive ideological mantra seems to lie at the heart of much of their work.

Much greater transparency of the actual allocated amount of funding is also required. Where is that funding going to, and how much of it is kept to finance Commonwealth, State, Territory and Non-Government Organisation bureaucracies and how much ends up ‘on the ground’? Why does the Commonwealth fail to publish a comprehensive budget list of all the programs funded under the National Plan? And why is there no clear statement from the Commonwealth under the National Plan regarding individual State and Territory statistics of increase or decrease in the rates of domestic violence and sexual assault?[58] These are all matters to be addressed for the future.

Conclusion

It is not currently possible to state with any degree of confidence that the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 has had any major impact at reducing levels of domestic violence or sexual assault within Indigenous communities across Australia at all. This should be of grave concern to all Australians.

In evaluating programs, perhaps qualitative data is more heavily relied upon because of the difficulty in accessing quantitative data, and the possible low skill level of some research and evaluation agencies in collecting, analysing and interpreting it. Further, the differing categorisation, collection, collation and publication methods between jurisdictions make the task even more difficult. Nevertheless, the current over-reliance upon subjective qualitative data, especially from agency sources, should be curtailed in favour of an objective assessment of measurable outcomes.

Have the Commonwealth, States and Territories expended a huge amount of funds for arguably little or no result, other than to provide employment for many staff, and business for many suppliers? As Hudson noted four years ago “Programs should not continue to be funded without evidence of any outcomes.”[59]

At the end of the day, the proof of the pudding is in the DV statistics. Are they going up or down? If they’re going down we can be confident the programs are working and are effective. If the statistics are still going up, we can be confident the programs are not working and the foundational problems are not being targeted. That much is sure.

[1] Hudson, S. (2016). Mapping the Indigenous program and funding maze. CIS Research Report RR18. Sydney, NSW: Centre for Independent Studies. p 1.

[2] Hudson, S. (2017). Evaluating Indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. RR28. Sydney NSW: Centre for Independent Studies. p 1.

[3] Hudson, S. (2016). op cit.

[4] Australian Government. (2020). Webpage.

[5] Most references in the National Plan, and in other sources and agencies, refer to ‘women and their children’, apparently not acknowledging that children are also the fathers.

[6] Australian Government. (2011). p 10.

[7] Australian Government. (2020). Webpage.

[8] Australian Government. (2013). National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children: Progress Report 2010-2012. Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. p. 12. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2013/final_edited_report_edit.pdf

[9] Australian National Audit Office. (2019). Auditor-General Report No.45 2018–19 Coordination and Targeting of Domestic Violence Funding and Actions. P 17.

[10] Ibid. p 42.

[11] https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/ofw/budget-2019/ofw-2019-budget-safety-security.pdf

[12] Australian Government. (2011). p 33 and Department of Social Services. (2014). p 3.

[13] See Australia Bureau of Statistics. (2014).

[14] See Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018).

[15] Australian Government. (2011). p 20.

[16] Health Outcomes International. (2014). National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022: Evaluation Plan. Glynde, SA: Health Outcomes International.

[17] Health Outcomes International. (2014). p 1.

[18] KPMG. (2017). Evaluation of the Second Action Plan of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022: Final Evaluation Report. Melbourne, Vic.: Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler for the Department of Social Services.

[19] Ibid. p 13.

[20] Ibid. p 14.

[21] Australian National Audit Office. (2019) Coordination and Targeting of Domestic Violence Funding and Actions Department of Social Services. The Auditor-General Report No.45. 2018–19 Performance Audit. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

[22] Ibid. pp 8-9.

[23] Ibid. p 9.

[24] Ibid. p 36.

[25] Ibid. p 10.

[26] Ibid. p 50.

[27] Ibid. pp 8-11.

[28] Putt, J., Holder, R. and Shaw, G. (2017). Alice Springs Integrated Response to Family and Domestic Violence project. Final Report. Armidale, NSW:University of New England.

[29] Ibid. p 44.

[30] Ibid. p 44.

[31] Ibid. p 69 & A3: 9-12.

[32] https://www.tangfamilyviolenceprevention.com.au/resources

[33] Nettelbeck, N. (2017). Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group Program Evaluation Report. Alice Springs, NT: Matrix on Board Consulting.

[34] Ibid. p 6-10.

[35] Ibid. p 7 & pp 23-24.

[36] Ibid. p 23.

[37] Ibid. p 25.

[38] Brown, C. (2019). Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program: A Case Study. 2019 Final Report. Canberra, ACT: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. Australian National University. p 48.

[39] Ibid. p 4-5.

[40] Ibid. p 49.

[41] Ibid. p 7.

[42] Ibid. pp 9-10.

[43] Our Watch, (2018a, b, c & d).

[44] No To Violence. (2020).

[45] Brown, C. (2019). Ibid. p 48.

[46] See also Price, J. (2016). pp 1-2.

[47] Willis, M. (2011). Non-disclosure of violence in Australia Indigenous communities. Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice. No. 405. Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Criminology. p 4.

[48] See Tucci (2017). ‘Explanatory Frames to understand family violence in Aboriginal communities’ p 50.

[49] Source: ABS. (2019a). 4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018. 27 June 2019.

[50] Source: ABS. (2019b). 4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018. 27 June 2019.

[51] Source: ABS. (2019c). 45100DO004_2018 Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018. Table 16 Victims, Selected offences by Indigenous status, Selected states and territories, 2010–2018.

[52] Source: Northern Territory Crime Statistics. (2020). Data through January 2020 Dept of the Attorney-General & Justice. p 35.

[53] Ting, et al. (2020).

[54] Knaus, C. (2019).

[55] This distinction should not be seen as ‘racist’ but as a means to better target programs and funding.

[56] See also Dodson, M. (2003). p 8.

[57] Purtill, T. (2017). pp 138-143.

[58] Some of this information can be ascertained after much trawling through ABS and State and Territory statistics, but they are not easy to access or interpret.

[59] Hudson. S. (2016). p 28.

Appendix A

Four National Plan Funded ANROWS Indigenous Projects:

- Advocacy for safety and empowerment: Good practice and innovative approaches with Aboriginal women experiencing family and domestic violence in remote and regional Australia.

Chief Investigator: Dr Judy Putt, University of New England.

Budget: $245,000 (Approx). Completion Date: March 2017.

https://www.anrows.org.au/project/advocacy-for-safety-and-empowerment-good-practice-and-innovative-approaches-with-aboriginal-women-experiencing-family-and-domestic-violence-in-remote-and-regional-australia/ - Improving family violence legal and support services for Indigenous women

Chief Investigator: Professor Marcia Langton, University of Melbourne.

Budget: $199,415 Completion Date: January 2020.

https://www.anrows.org.au/project/improving-family-violence-legal-and-support-services-for-indigenous-women/ - Improving family violence legal and support services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men who are perpetrators of family violence

Chief Investigator: Professor Marcia Langton, University of Melbourne.

Budget: $199,819 Completion Date: February 2020.

https://www.anrows.org.au/project/improving-family-violence-legal-and-support-services-for-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-men-who-are-perpetrators-of-family-violence/ - Understanding the role of law and culture in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander communities in responding to and preventing family violence.

Chief Investigator: Professor Harry Blagg, University of Western Australia.

Budget: $284,836.80 Completion Date: May 2020.

https://www.anrows.org.au/project/understanding-the-role-of-law-and-culture-in-aboriginal-and-or-torres-strait-islander-communities-in-responding-to-and-preventing-family-violence/

This is a total Budget in excess of $684,315.00 for three universities. The research in Project 2 provides for small sample groups, and the relevance of research into Victorian Aboriginal people may have little relevance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across the rest of Australia. Much of the grant funding will be spent on staffing, office rental, airfares, car hire, taxis, meals, accommodation, stationery, computers and other resources. Is this money well spent in achieving the goals of the National Plan?

Of course research must be conducted; however, this type of research, all led and conducted by University academics, continues year in – year out, and yet the benefits ‘on the ground’ in reducing domestic violence and assault statistics have yet to be demonstrated. Arguably, some of the research outcomes may even be counter-productive.

Appendix B

Australian National Audit Office Evaluation Report Recommendations to the Department of Social Services.

Note that references to ‘data’ do not specify quantitative or qualitative types.

| Recommendation no. 1 Paragraph 3.32 | The Department of Social Services specify research and data projects as actions under each of the priority areas agreed by governments for the Fourth Action Plan. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

| Recommendation no. 2 Paragraph 3.67 | The Department of Social Services, in consultation across governments, develop a National Implementation Plan for the Fourth Action Plan. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

| Recommendation no. 3 Paragraph 4.10 | The Department of Social Services identify and develop new measures of success, data sources and specific outcomes for the Fourth Action Plan, and any future National Plan. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

| Recommendation no. 4 Paragraph 4.45 | The Department of Social Services work with the states and territories to plan evaluations of individual services and programs funded across jurisdictions under action plans to inform an outcome evaluation of the Fourth Action Plan and overall National Plan. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

| Recommendation no. 5 Paragraph 4.61 | That public annual progress reports for the Fourth Action Plan document the status of each action item and the outcomes of the National Plan as a whole. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

27. The proposed report was provided to the Department of Social Services (DSS). The summary response from DSS is set out below:

“The department is committed to building on what the ANAO acknowledges are the effective governance arrangements already in place to support implementation of the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan). The report’s insights will help strengthen the final development phase and subsequent implementation of the Fourth Action Plan of the National Plan.”[60]

One can only wonder at how such broad motherhood statements will be implemented, translated into effective outcomes, and properly evaluated.

[60] Australian National Audit Office. (2019) Coordination and Targeting of Domestic Violence Funding and Actions Department of Social Services. The Auditor-General Report No.45. 2018–19 Performance Audit. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia. Pages 10-11.

References:

Australia Bureau of Statistics. (2014). 4529.0.00.003 – Foundation for a National Data Collection and Reporting Framework for family, domestic and sexual violence, 2014. Canberra, ACT: Australia Bureau of Statistics.

https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/4389FE474480EFD2CA257D5F00189DE7?Opendocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). 4533.0 – Directory of Family, Domestic, and Sexual Violence Statistics, 2018. Canberra, ACT: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4533.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019a). 4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018. 27 June 2019.

https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4510.0Main+Features12018?OpenDocument

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019b). 4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018. 27 June 2019.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019c). 45100DO004_2018 Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2018. 27 June 2019. Table 16 Victims, Selected offences by Indigenous status, Selected states and territories, 2010–2018.

https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4510.02018?OpenDocument

Australian Government. (2011). National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children: Including the first three-year Action Plan. Canberra, ACT: Department of Social Services.

https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/08_2014/national_plan1.pdf

Australian Government. (2013). National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children: Progress Report 2010-2012. Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2013/final_edited_report_edit.pdf

Australian Government. (2020). National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children. (webpage). https://plan4womenssafety.dss.gov.au/the-national

-plan/what-is-the-national-plan/

Australian National Audit Office. (2019). Coordination and Targeting of Domestic Violence Funding and Actions Department of Social Services. The Auditor-General Report No.45. 2018–19 Performance Audit. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/coordination-and-targeting-domestic-violence-funding-and-actions

Brown, C. (2019). Tangentyere Family Violence Prevention Program: A Case Study. 2019 Final Report. Canberra, ACT: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. Australian National University.

and https://www.tangfamilyviolenceprevention.com.au/resources

Department of Social Services. (2014). Domestic Violence in Australia Submission 57 – Attachment 3. Progress Review of the First Action Plan of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022 May 2014. https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=166239c4-c120-48fc-84bc-d8304859ea91&subId=298614

Dodson, M. (2003). Violence Dysfunction Aboriginality. Canberra, ACT: Address delivered to the National Press Club.

http://ncis.anu.edu.au/_lib/doc/MD_Press_Club_110603.pdf

Health Outcomes International. (2014). National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022: Evaluation Plan. Glynde, SA: Health Outcomes International. https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/women/programs-services/reducing-violence/the-national-plan-to-reduce-violence-against-women-and-their-children/evaluation-plan-for-the-national-plan-developed-by-health-outcomes-international

Hudson, S. (2016). Mapping the Indigenous program and funding maze. CIS Research Report RR18. Sydney, NSW: Centre for Independent Studies. https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2016/08/rr18-Full-Report.pdf

Hudson, S. (2017). Evaluating Indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. CIS Research Report RR28. Sydney, NSW: Centre for Independent Studies. https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2017/06/rr28.pdf

Knaus, C. (2019). Northern Territory refusing one in four FOI requests – seven times Victoria’s rate. The Guardian. 7 Jan 2019. Sydney, NSW: Guardian Media Group. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jan/07/northern-territory-refusing-one-in-four-foi-requests-seven-times-victorias-rate

KPMG. (2017). Evaluation of the Second Action Plan of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022: Final Evaluation Report. Melbourne, Vic.: Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler for the Department of Social Services. https://www.dss.gov.au/women/publications-articles/evaluation-of-the-second-action-plan-of-the-national-plan-to-reduce-violence-against-women-and-their-children-2010-2022

Nettelbeck, N. (2017). Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group Program Evaluation Report. Alice Springs, NT: Matrix on Board Consulting. https://www.tangfamilyviolenceprevention.com.au/uploads/pdfs/Matrix_TWFSG-Evaluation-Final.pdf

No To Violence. (2020). About Us. https://www.ntv.org.au/about-us/

Northern Territory Crime Statistics. (2020). Data through January 2020 Dept of the Attorney-General & Justice.

Our Watch. (2018a). Changing the Picture, Background paper: Understanding violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Melbourne, Vic.: Our Watch.

Our Watch. (2018b). Changing the picture: A national resource to support the prevention of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children. Melbourne, Vic.: Our Watch.

Our Watch. (2018c). Change the Story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia. Melbourne, Vic.: Our Watch. https://www.ourwatch.org.au/change-the-story/

Our Watch. (2018d). ReflectReconciliation Action Plan: July 2017 – July 2018. Melbourne, Vic.: Our Watch.

https://www.ourwatch.org.au/resource/reconciliation-action-plan

Price, J. Y. N. (2016). Homeland truths: The unspoken epidemic of violence in Indigenous communities. Helen Hughes Talk for Emerging Thinkers. CIS Occasional Paper 148. Sydney, NSW: Centre for Independent Studies.

Putt, J., Holder, R. and Shaw, G. (2017). Alice Springs Integrated Response to Family and Domestic Violence project. Final Report. Armidale, NSW:University of New England.https://rune.une.edu.au/web/handle/1959.11/20866

Purtill, Tadhgh. (2017). The Dystopia in the Desert: The silent culture of Australia’s remotest Aboriginal communities. Melbourne, Vic: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Ting, I., Scott, N. and Palmer, A. (2020). Rough justice: How police are failing survivors of sexual assault. ABC News.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-28/how-police-are-failing-survivors-of-sexual-assault/11871364

Tucci, J., Mitchell, J., Lindeman, M., Shilton, L. and Green, J. (2017). Strengthening Community Capacity to End Violence: A Project for NPY Women’s Council. Alice Springs, NT: NPY Women’s Council and Australian Childhood Foundation. https://www.npywc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/Strengthening-Community-Capacity-to-End-Violence-26june18.pdf

Willis, M. (2011). Non-disclosure of violence in Australia Indigenous communities. Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice. No. 405. Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Criminology. https://aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi405